- Home

- Stuart Methven

Laughter in the Shadows Page 2

Laughter in the Shadows Read online

Page 2

“But this time he won’t get away with it. I am going to bring this up with the Grievance Committee, and they will take my complaint to the plant superintendant, who will order your boy foreman to slow the conveyor and stop running the Gumshoe Department like a sweatshop!

“And Nell won’t have to cry anymore!”

Ray would pat Nell on the back, raise his hands over his head like a victorious boxer, and leave. Ray was the hero; I, the hissed villain.

Sometimes, on the way out, when no one was looking, Ray would wink at me.

When I saw Ray coming toward us while we were watching the softball game, I wondered what the Italian bugbear was up to. Ray slapped me on the back like we were old friends, then introduced himself to Joy, turning on the Mediterranean charm that kept getting him reelected as union steward.

I decided to ignore Ray and turned back to watch the game. I had little trouble overhearing Ray as he invited Joy for a homemade spaghetti dinner one evening, adding that she could bring her husband along. Ray was probably aware I was listening, because he quickly lowered his voice so I could catch only parts of what he was saying about “your husband’s problem … harassing workers … making women cry,” and then, raising his voice, he added, “If he doesn’t change his ways, he would probably end up in the vulcanizer … come out shriveled up like a prune!”

Ray had gone too far and I turned to confront him. Unfortunately, he was already walking away after telling Joy he was “only kidding” about the vulcanizer and not to forget his invitation for a spaghetti dinner.

Ray had succeeded in ruining the picnic, having described me to Joy as a slave-driving Simon Legree and a candidate for the vulcanizer. I had already heard tales circulating around the mill and local bars about vulcanizer “accidents” and had no trouble imagining the satanic grin on Ray’s face as I was wheeled into my fiery immolation.

I decided to leave the picnic early before the display of fireworks. When we got home, I went straight to the basement and began rummaging through the boxes we still hadn’t unpacked until, at the bottom of one of them, I found what I was looking for: a fat manila envelope containing a thirty-seven-page questionnaire.

The next three nights I spent filling out the questionnaire, calling my parents for details and dates of my early bed-wetting habits, childhood illnesses, school records, and so forth. My father’s memory was as porous as mine, but my mother was an inveterate pack rat and still had my old vaccination records, school report cards, and certificates of Boy Scout merit badges.

I filled out the thirty-seven pages, signed at the bottom attesting that “all the information was true and correct to the best of my knowledge,” and sent it off to Washington.

Two weeks later a telegram arrived requesting that I come to Washington for an interview. It didn’t inquire why it had taken me over a year to fill out the questionnaire.

The sign on the anchor-fence at 1410 E Street read Naval Research Facility. A guard at the gate pointed to the brick mansion with white pillars at the end of a circular driveway. It looked like an antebellum plantation manor. A receptionist sat at a desk under a large chandelier that hung from a flaking gilt ceiling. A spiral staircase, where southern suitors had awaited the descent of their Scarletts, led to the second floor where my interview was to take place.

My interviewer was a bald man with Coke-bottle glasses. He motioned for me to sit down, offering a cup of coffee while he finished looking thorough the folder containing my questionnaire. He closed the folder, leaned forward, and said he had only one question: “How do you feel about jumping out of an airplane?”

I was caught off guard by what was probably a trick question. I remembered a war story about D-day. A paratrooper had got caught on a church steeple, leaving him hanging helplessly, prey for German snipers. I told the interviewer that parachute jumping sounded exciting. I didn’t add that it beat being vulcanized.

He jotted something in my folder and came around the desk to shake my hand. “Welcome to the CIA!”

He told me I had been selected for a “high priority” Agency program. My clearance was being expedited, and I could count on “coming on board” within sixty days. When I returned to Naugatuck, I didn’t tell anyone I would be leaving because I didn’t want to burn that bridge to the general foreman’s job if the CIA clearance didn’t come through. A month later I received a telegram advising me that my clearance had come through. I was to report to Washington as soon as possible.

The rubber company personnel director couldn’t understand why I was passing up the chance to become a general foreman. I pointed to the “DON’T DIE ON THIRD!” sign over his desk and said that third base for me was the Gumshoe Department, and I needed to move on.

The Gumshoe Department gave me a farewell party. Nell cried “for old times’ sake,” and I proposed a toast to my good friends in the department, including the union steward, adding that “every college boy needs a Ray Mengacci in his life!” I winked at Ray.

We packed up the Pontiac, strapped five-month-old Laurie into the car seat, took a last breath of Naugahyde, and headed off for Washington.

When I arrived at the E Street entrance, I noticed for the first time the more imposing Department of State building across the street. With its Italian marble front, spacious lobby, and queue of limousines in the driveway, it stood in dignified contrast to its upstart neighbor hiding behind the Potemkin front of a “Naval Research” facility.

The same receptionist handed me a clipboard of forms to fill out. Most were routine forms having to do with bank deposits, health insurance, the credit union, and who to advise in case of death. The last form was a Secrecy Agreement binding me not to reveal my CIA employment to anyone and never to speak or write about any of my activities in the CIA without permission.

I balked at the monastic vow binding me to forever sheathe my pen and seal my lips. Even Alice was able to recount her adventures after she emerged from the rabbit hole. I bit my tongue and signed.

I handed in the form and went down the hall to be given a polygraph and a physical exam, and at the end of the day, I was sworn in.

CHAPTER 2: Training

Think back: We all became spies as children: that’s the only way we know to make sense of the world.

—AMANDA CROSS, An Imperfect Spy

The new recruits boarded the Agency’s Blue Bird bus for the trip across town to the training site, an amphitheater in a park near the Potomac River. The amphitheater, set behind a clump of trees, was barely visible from the road. The chimes of the Netherlands carillon were the only sounds breaking the silence.

Guards checked our newly issued badges on the way in, trying in vain to match photos with faces. Inside we filed into an auditorium, our classroom for the two-month orientation course.

First, however, we were given our pseudonyms. Every Agency officer is christened with a pseudonym, the alter ego he will carry with him throughout his career. He will be paid in pseudonym, cited in dispatches in pseudonym, reprimanded in pseudonym, decorated in pseudonym, and retired or terminated in pseudonym.

Pseudonyms are selected from a list of names on file in Registry. One officer in our group didn’t like the pseudonym he had been given, Carl RAINTREE, because he thought it implied Apache ancestry. When he asked for another pseudonym, he was told a pseudonym could not be changed unless it was “compromised.” The officer then deliberately left his pay slip with his RAINTREE pseudonym out on his desk. The slip was discovered and turned in by the night security guard. RAINTREE was reprimanded, given a security violation, and assigned a new pseudonym: Jerome P. TWADDLEDUCK.

We were given the outline of a cover story we were to use with outsiders. The cover story, a fable woven from half truths, was in the early 1950s a device designed to deflect Russian KGB agents in their attempts to identify CIA officers. In practice, however, the cover story confounded friends and neighbors more than it did the Russians.

My cover story, which I laid on with my next-do

or neighbor, was that I was an analyst with the Defense Department. Unfortunately, as it turned out, my neighbor was truly employed by the Defense Department, and he responded to my story by asking me to join his car pool to the Pentagon. When I begged off, citing odd working hours, he asked me to meet him for lunch in the Pentagon cafeteria and again I had to put him off. He finally saw through my “Defense analyst” charade and resigned himself to having a “spook” as his neighbor.

My relatives, particularly my in-laws, were not as understanding. They became convinced, as I kept changing cover stories with each new assignment, that I couldn’t hold down a steady job.

The Curriculum

Long before Moses sent spies into Canaan, Sumerian rulers were sending out agents to bedevil their opponents. There seems in fact to have been no period in history during which secret agents have not played a part in political and military affairs.

—ERIC AMBLER, Epitaph for a Spy

The course opened with a history of the world’s “second oldest profession.” The earliest recorded agent operations, documented in the Dead Sea Scrolls, were run by Moses, who recruited “agents” to reconnoiter routes to walk across the Red Sea. Stick-figure cave scratchings of spear-carrying warriors illustrated prehistoric paramilitary operations. Julius Caesar was extolled for creating the first military intelligence (G-2) branch, which was instrumental in his conquest of Gaul. His Praetorian successors, however, were faulted for serious “intelligence failures” in underestimating the capabilities of the barbarians at the gate.

The Espionage Hall of Fame inductees included Nathan Hale, Benedict Arnold, Mata Hari, and Kim Philby.

My Oscar for training films went to “The Tawny Pipit,” starring two rara avis pipits, surveillance targets of a team of ornithologists. The two bird-watchers suffered the damp cold and biting winds of the Scottish highlands for over a year, recording the feeding and sexual habits of the pipits. The ornithologists even ran a bugging operation, slipping two egg-shaped microphones into the nest. As an audio operation, it was a failure, however, because the pipits disdainfully pecked out the “bugs” and dropped them into the bog.

Sessions on “tradecraft” covered recruitment of agents (beware of “dangles” and “doubles”), clandestine meetings (don’t arrange rendezvous “under the old oak tree,” which may have perished from elm rot), danger signals (avoid using the upside-down “For Rent” sign in the window, which the cleaning woman probably will probably put back right side up), and dead drops (don’t use air conditioners, which are too often sent out for repairs with the coded message inside).

The course lasted four weeks. When it was over, eighteen of us were taken aside and told we were being sent to The Farm for a six-month “special training” course. We were to “pack light” and be ready to leave the following Monday.

The Farm

Lest men suspect your tale to be untrue,

Keep probability—some say—in view.

… Assemble, first, all casual bits and scraps

That may shake down into a world perhaps;

… Let the erratic course they steer surprise

Their own, and your own and your readers’ eyes;

—ROBERT GRAVES, The Devil’s Advice to Story-tellers

Leaving our wives, companions, and children behind to cope with Washington living (we had rented a row house on 5th and Peabody Street, next door to a high school principal and his wife who promised to look after Joy and eighteen-month old Laurie), we departed for special training at a secret site. The location of the site was no secret to our wives, who were able to easily pinpoint the location by interrogating their husbands about the length of time of the bus ride, the local climate, topography, and so forth. And although the training site was secret in the beginning, stories later appeared in the press alluded to the CIA training site in southeastern Virginia.

After a three-hour bus ride, “WARNING: U.S. GOVERNMENT PROPERTY” signs began to appear. A mile or so later we turned in at a gate and were waved through by security guards. After a twenty-minute ride winding through a pine forest, the bus emerged in front of a quadrangle of barracks: The Farm.

Thumping a swagger stick, a leather-faced figure stood by the bus as we got off. He immediately barked at us to line up and stand at attention. Once we had formed up to his satisfaction, the gravel-throated officer walked back and forth in front of us, stopped, and spoke.

“Welcome to The Farm. My name is Hodacil. I will be your supervisor, disciplinarian, and chaplain. You are here for six months. Reveille is at six. Physical training at six thirty, followed by a three-mile run. After breakfast, you begin your training in ‘candlesteen’ warfare with courses on weapons, explosives, sabotage, living off the land, silent killing, parachute jumping.

“After six months, you will undergo a three-week comprehensive field exercise when you will live off the land and put in practice those ‘candelsteen’ techniques. After the ‘COMP’ is over, you will return to D.C.

“One last thing. You can quit any time. But while you’re here, you will do what I tell you, when I tell you. Don’t smart-ass me, and remember, you can’t shit an old shitter!”

For the next six months we remembered.

I wondered if I had gotten on the right bus. Silent killing? Sabotage? I had thought this special training was going to be about recruiting agents in Viennese Rathskellers and pilfering secrets in Istanbul souks. I looked around at our group. One or two could be smoke jumpers or linebackers, but most were nondescript school teachers, bank clerks, or management trainees. None looked like potential saboteurs or silent killers.

I had no time to reflect, however. Hodacil was barking for us to double-time over to the mess hall.

Bert

My eyelids were still crusted when Hodacil rousted us out the next morning for physical training. Bert, the instructor, looked like Charles Atlas in the ad about “making MEN out of ninety-eight-pound weaklings!” He was bald and barrel-chested. His neck was so thick it was hard to tell where it ended and his shoulders began, and his top-heavy torso obscured the wiry muscled legs that pumped up and down while he led our exercises.

Bert had been a Presbyterian minister and lived by the credo that the human body was a gift from God and abusing or neglecting it was a sin. His physical prowess was legend at The Farm, where he dove through ice-crusted ponds to retrieve ducks shot by fellow instructors and dropped them at their feet like a faithful Labrador.

I was a disappointment to Bert. I made it through the push-ups and duck-walks and wheezed along the three-mile run. But I failed him on the obstacle course, a satanic steeplechase of greased poles to shimmy up, ravines, and three walls. The ten-foot wall was my nemesis.

I could vault over the six-foot wall, pull myself up and over the eight-foot wall, but the ten-foot wall stymied me. Others danced up the barrier like Jimmy Cagney in Yankee Doodle Dandy, but I always bounced off and landed on my back as the rest of the group ran by, splattering mud on their prostrate classmate.

The forays against the ten-foot wall took a toll on my rib cage, and I began sneaking around the wall when Bert wasn’t looking. One day, however, Bert caught me as I was making my furtive detour. He had a pained look on his face and called me over to where he was standing. “St. Martin,” he said. “one day you will find yourself in a gulag behind a wall like that one. If you can’t make it over, you will spend the rest of your life in a Siberian stalag. Now get back there and try again. And again. And again, until you make it over that wall.”

I wanted to tell Bert about my battered rib cage, but he would have just told me to “work it out,” so I went back to try again. I crouched down, dug in my toes, and ran toward the wall. My momentum almost carried me over, but as I grabbed for the top, I slipped and fell, hitting the ground hard. The wind was knocked out of me, and my eyes began to water, and I could just make out Bert standing there, unmoved.

His stone-faced look angered me, probably as Bert intended. I picked myself up a

nd went back for another try. Pawing dirt and snorting, I took a deep breath and ran. I hit the wall so hard I was carried straight up, and suddenly I found myself on top. I swung my leg over and, for a moment, just sat there savoring my triumph. Then I dropped down on the other side, where Bert stood waiting, a trace of a smile on the ex-pastor’s face. We jogged together the rest of the way, and at the end of the course Bert pressed a piece of paper in my hand, a poem he had copied by hand:

It’s the plugging away that will win you the day

So don’t be a piker old pard:

Just draw on your grit, it’s easy to quit,

It’s the keeping the chin up that’s hard!

I ran into Bert ten years later on another obstacle course called Vietnam, where “keeping the chin up was hard.”

The formal course began with weapons training, learning how to assemble, disassemble, and fire Russian Kalashnikovs, Israeli Uzis, American violin-case Thompson submachine guns, and “Swedish Ks.”

I was told that covert merchants had fanned out during the Cold War, buying up weapons of foreign origin, including a large number of Swedish K submachine guns. A number of these “sterile” weapons were allegedly stored behind the Iron Curtain and later reportedly unearthed by KGB canines. Some remain buried to confound future archaeologists.

Lanavoski (Ski) taught us the “art of silent killing.” To Ski the jewel of the crown was the stiletto, which, when inserted into the jugular, would dispatch the victim without a gurgle. One volunteer for Ski’s stiletto demonstration still bears a four-pointed scar on his neck as a reminder of Ski’s “jewel.”

The Survival Course was a welcome change. We spent two weeks in the field learning carving fishhooks, setting snares, and cooking three-star bouillabaisses of grub worms.

Suturing

Holmes had more than once left the classroom when a live rabbit was to be chloroformed beseeching his demonstrator not to let it squeak.

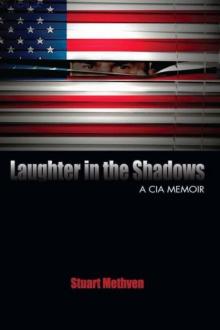

Laughter in the Shadows

Laughter in the Shadows